Of all the distinguished military men who came from abroad to fight for the independence of the thirteen colonies, Thaddeus Kosciuszko (Kos-choos-ko) of Poland was the first. He came to Philadelphia and offered his services to the Continental Congress in August, 1776, and he served continuously until the end of the war, seven years later. He earned praise from George Washington and the special thanks of Congress. Then he returned to Poland, became head of the government and commander-in-chief of the army in the Insurrection of 1794, winning a place in Polish history comparable to that of Washington in the United States. Acclaimed throughout the world as a courageous fighter for freedom, Kosciuszko came back to visit America in 1797 and lived for nearly six months in Philadelphia, then the capital of the nation. The modest brick house in which he stayed at Third and Pine Streets is now preserved by the National Park Service as the Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial.

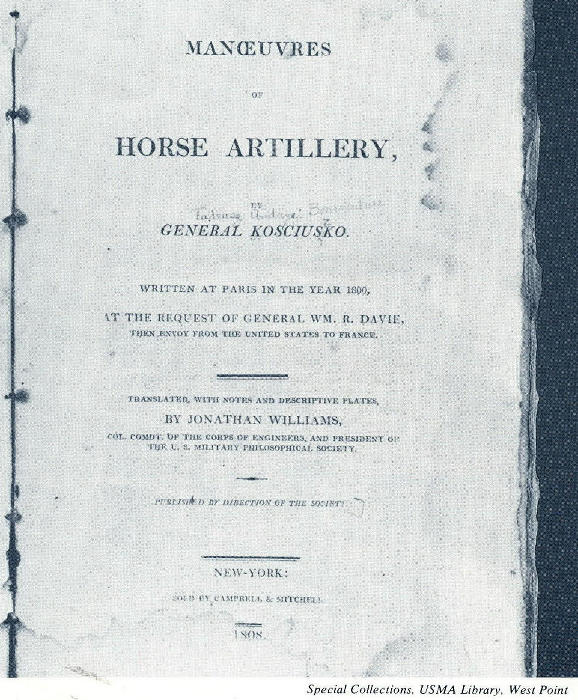

Of all the distinguished military men who came from abroad to fight for the independence of the thirteen colonies, Thaddeus Kosciuszko (Kos-choos-ko) of Poland was the first. He came to Philadelphia and offered his services to the Continental Congress in August, 1776, and he served continuously until the end of the war, seven years later. He earned praise from George Washington and the special thanks of Congress. Then he returned to Poland, became head of the government and commander-in-chief of the army in the Insurrection of 1794, winning a place in Polish history comparable to that of Washington in the United States. Acclaimed throughout the world as a courageous fighter for freedom, Kosciuszko came back to visit America in 1797 and lived for nearly six months in Philadelphia, then the capital of the nation. The modest brick house in which he stayed at Third and Pine Streets is now preserved by the National Park Service as the Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial. Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial 1776 - 1783 Kosciuszko set out for America after hearing of the 1775 fighting at Lexington and Concord. He was already on his way across the Atlantic when the Continental Congress in Philadelphia adopted the Declaration of Independence. He was in Philadelphia before the end of August, and on August 30 at Independence Hall his "memorial" or petition was read in Congress requesting an assignment in the army of General George Washington.  Kosciuszko was then 30 years old, the youngest son of a Polish family of noble background but limited wealth. He was a skilled military engineer trained in Poland and in graduate academies in France. He knew French and German as well as Polish and he soon learned to converse in English, although he never wrote it fluently. He was polished in manners, modest in nature, knowledgeable in science and an amatuer artist. While Congress considered his request for a place in the army, Kosciuszko was pressed into service by the worried Council of Safety in Philadelphia. New york had fallen to the British; General Washington was retreating across New Jersey; and an assault upon Philadelphia was expected both by land and by British gunboats in the Delaware River. The Polish engineer helped block the river, first by building fortifications on Billingsport Island just below the city, later by strengthening defenses on the New Jersey shore at Red Bank (Fort Mercer). On October 18, 1776, Congress voted Kosciuszko's commission as Colonel of engineers in the continental army.  Congressional Record, 1776 showing Kosciuszko's request and approval of commission into the Continental Army From Albany, Kosciuszko was promptly dispatched further north to Fort Ticonderoga, the strategic post which Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys had captured so sensationally from the British in 1775. Introducing Kosciuszko to the commanding officer at Ticonderoga, Gates wrote: He is an able Engineer, and one of the best and neatest draughtsman I ever saw. I desire he may have a Quarter assigned him, and when he has thoroughly made himself acquainted with the works, have ordered him to point to you, where and in what manner the best improvements, and additions can be made thereto…British strategy was to send General John Burgoyne south from Montreal by way of Lake Champlain and the Hudson to capture Albany and link up with other British forces from the west and from New York City. George Washington regarded the Hudson pathway as the most important line of defense in America. Ticonderoga was a key spot. Kosciuszko reported, however, that it was vulnerable. The fortress was overlooked by a steep and rocky hill ( now called Mount Defiance) which was unprotected. The Polish engineer wanted a battery of guns mounted at the top. General Gates agreed, but at that juncture had to return temporarily to duty in Philadelphia. Other senior officers decided against Kosciuszko’s recommendations. To haul heavy guns to the top would be a long and difficult task. In the time remaining before expected attack, they concluded, neither sufficient manpower nor equipment was on hand. When Burgoyne’s army abruptly appeared before Ticonderoga late in June, Kosciuszko’s point was proved. Within five days, British guns were in place on the Mount, aimed down at the interior of the fort. An American council of war decided unanimously that Ticonderoga could not be held under the circumstances, and during the night of July 5 the entire garrison abandoned Fort Ticonderoga, leaving it open to the British. The blow was a devastating one to the cause of the Revolution. Loss of the Fort without a fight brought a storm of abuse in Congress and a court martial of General Arthur St. Clair, who had been temporarily in command of the Fort at the time. Kosciuszko was one of the witnesses at the trial. His testimony was without bitterness. He understood St. Clair’s position, even if he did not agree with it. St. Clair was exonerated. Throughout July, 1777, the northern army retreated steadily, sometimes in disorder, harassed by Burgoyne’s troops and by his Indian allies. Kosciuszko prepared a series of new campsites, each further south, until in August the American army had withdrawn to within nine miles of Albany. It became essential that a new and strong defensive position be established on the Hudson, and General Gates was ordered back to Albany to take charge. Gates promptly ordered the demoralized troops to move northward again. He sent Kosciuszko and Colonel Hay on ahead “to select a position on the western bank of the Hudson, which from its hilly and covered surface, would be best suited for defense.” Gates’ Quartermaster, General Morgan Lewis years later related: “They rode up the hill and examined the grounds on Bemis Heights, and Kosciuszko decided immediately that that was the proper position for a fortified camp. He inquired the number of divisions and regiments in the Army and their names, took a piece of paper from his portfolio, and drew in pencil the plan of the camp, and assigned the location of several regiments and in conformity with that plan they were speedily marched to the ground and they proceeded to erect breastworks and fortifications…”When General Burgoyne’s redcoats approached from the north, Kosciuszko’s defenses were ready. The Americans were positioned on Bemis Heights at a narrow place in the river about seven miles below the village of Saratoga (now called Schuylerville). The only north-south road was squeezed tight against the river at that point and exposed to gunfire from the hills. Burgoyne was unable to make his way around the Americans and was forced to attack the a strongly defended position. The first day’s bloody fighting occurred on September 19, 1777. British soldiers with fixed bayonets made charge after charge, but were repulsed. At night they were still some two miles north of the American lines on Bemis Heights. Burgoyne delayed nearly three weeks, hoping that the other British forces in New York would bring him relief, but it never came. With his base far behind in Canada and his supplies running low, Burgoyne made a final, desperate attempt to outflank the American position and to force his way to Albany, but Kosciuszko’s defenses held. The British retreated and were surrounded in camp near Saratoga. There, on October 17,1777, Burgoyne surrendered the entire British force of 6000 troops. Historians have called Saratoga one of the world’s most decisive battles. It changed the course of the American Revolution, persuaded France and Spain to come to the aid of the Americans, and made Independence a reality. General Gates was everywhere celebrated for the triumph; some began to think that he, rather than Washington, should be commander-in-chief; but Gates understood the situation. While being praised extravagantly by a Philadelphia doctor, he cut off the compliments by saying: “Stop. Stop. Let us be honest. In war, as in medicine, natural causes not under our control do much. In the present case, the great tacticians of the campaign were hills and forests, which a young Polish Engineer was skillful enough to select for my encampment.”A celebrated painting of Burgoyne’s surrender hangs in the national capital in Washington. The Artist: John Trumbull, one of Kosciuszko’s fellow officers in the northern campaign.  Burgoynes Surrender  Thaddeus Kosciuszko Monument - Saratoga, N.Y. 1746-1817 IN MEMORY OF THE NOBLE SON OF POLAND BRIG. GENERAL THADDEUS KOSCIUSZKO MILITARY ENGINEER SOLDIER OF THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE WHO UNDER COMMAND OF GENERAL GATES SELECTED AND FORTIFIED THESE FIELDS FOR THE GREAT BATTLE OF SARATOGA IN WHICH THE INVADER WAS VANQUISHED AND AMERICAN FREEDOM WAS ASSURED . . . ERECTED BY HIS COMPATRIOTS A.D. 1936 Soon after the victory at Saratoga, it was decided that the new, permanent fortification on the Hudson would be built further south at West Point. Kosciuszko was sent there as chief engineer in March, 1778 and remained for 28 months. He was charged with planning and building hilltop forts, redoubts, gun emplacements, breastworks and troop barracks so strong as to eliminate any further danger of invasion from Canada. West Point became “The Gibraltar of America,” and the British never undertook to capture it. Some have said West Point was Kosciuszko’s greatest achievement because by preventing a battle, he saved lives on both sides. During the early part of his assignment at West Point, Kosciuszko’s work was pushed with emergency speed lest there be a British assault. Later, Washington established his headquarters nearby and the work proceeded in relative security at a more orderly pace. Washington himself was greatly interested in it. Kosciuszko escorted him on trips of inspection. After one of them in June, 1779, the following notice was posted: “Lost yesterday, reconnoitering with his Excellency, General Washington, a spur, with treble chains on the side, and a single one underfoot, all silver, except the tongue of the buckle and the rowel. Whoever has found, or shall find it, and will bring it to Colonel Kosciuszko or at headquarters, shall have ten dollars reward”.(At first, West Point was a fortress only. The Military Academy was not established there until 1802. When it was, the first cadets were all engineers. A treatise by Kosciuszko on employment of artillery was used as a text. The first monument erected at the Academy was a tribute to Thaddeus Kosciuszko commissioned and paid for by the cadets themselves. Cadet Robert E. Lee was one of those responsible. The monument still stands near a corner of the parade ground on the site of one of the forts Kosciuszko built.)  Kosciuszko Treatise on the Employment of Artillery  First monument erected at West Point Military Academy Thaddeus Kosciuszko In the summer of 1780, with his major work at West Point coming to an end, Kosciuszko wrote General Washington: “I beg your Excellency to give me permission to leave the Engineer Department and direct me a command in the light infantry…” Washington replied on August 3: …as there is a necessity for a Gentleman in the Engineering Department to remain constantly at that post, and as you from your long residence there are particularly well acquainted with the works and the plans for their completion, it was my intent that you should continue. The Infantry Corps was arranged before the receipt of your letter. The southern Army, by the captivity of Genl. du Portail and the other Gentlemen in that branch, is with out an Engineer, and as you seem to express a wish of going there rather than remaining at West Point, I shall, if you prefer it to your present appointment, have no objection to your going.Just about the time Kosciuszko left West Point, Benedict Arnold took over command there. The Polish engineer was on his way south when Arnold’s treacherous plot to betray West Point to the British was discovered. During his long service at West Point, Kosciuszko found recreation in building a small flower garden in the steep cliff overlooking the Hudson. The army doctor at West Point wrote of it “abounding more in rocks than in soil” and he told how Kosciuszko had turned a little spring into a “curious water fountain with spurting jets and cascades.”  Kosciuszko's Garden Kosciuszko’s garden and its tiny fountain are still perched on the side of the cliff, seldom seen by modern visitors. The location is just south of another Academy landmark much better known: Flirtation Walk. The Southern Campaign and War’s End During the final three years of the war, Kosciuszko served in the south as chief engineer to Nathaniel Greene, a General who moved troops swiftly and often, preferring water transportation when possible. The engineer was kept busy exploring rivers in the wilderness of the western Carolinas, finding new campsites, superintending construction of fleets of small boats. During Greene’s month-long siege of a small garrison named Ninety-six in North Carolina, Kosciuszko directed the day-by-day construction of a geometric pattern of trenches which enabled the attackers slowly to approach the fortress without exposure to gunfire. The siege was not successful, however, and had to be abandoned when British reinforcements arrived. Still to be seen are the remains of a tunnel or “mine” with which Kosciuszko hoped to blow up the main redoubt. After Lord Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown in October, 1781, Charleston, Savannah and other places remained in enemy hands and sporadic action continued for two more years. General Greene put Kosciuszko in command of a small detachment of infantry that figured in the raid on James Island, which has been called the last gunfight of the war. When the British finally evacuated Charleston in December, 1782, Kosciuszko led a parade of his men into the city. Released from Army service in June, 1783, Kosciuszko came to Philadelphia to wind up his affairs in America. He was promoted to Brigadier General and voted a special resolution of thanks by Congress. He was in New York when Washington made a triumphal entry into the city toward the end of 1783, and was at Faunces’ Tavern, there for the farewell of the Commander-in-chief. Along with other officers of Washington’s army, Kosciuszko became an original member of the Society of Cincinnati. He received two gifts from Washington: an engraved ceremonial sword and a handsome pair of pistols inscribed: 17 E Pluribus Unum 83”  These are still exhibted in Polish museums  When Kosciuszko sailed for home from New York on July 15, 1784, a fellow passenger wrote a letter with a rhymed report of the journey, including identification of all on shipboard, beginning with Kosciuszko: “Him first, known in war full well, The Kosciuszko Insurrection 1792-1794 When he returned to Poland in 1784, Kosciuszko wrote that “the affairs of the republick as well as mine are in a very horrid situation.” He lived a quiet and inactive life in his home village. But the reforms of the Great Diet of 1788 brought hope that his country could follow America’s example and throw off foreign domination. The Diet provided for an enlarged people’s army, and Kosciuszko accepted a General’s commission. When the new Constitution of May 3, 1791 was enacted, he and his command were among the first to swear allegiance to it. The rising spirit of Independence brought repression by the Russian Empress, Catharine the Great, whose troops invaded Poland in 1792. Kosciuszko was in the thick of the resistance. The King of Poland bestowed upon him the highest of Polish Military honors, the cross of Virtuti Militari in July, 1792. Yet only a few months later the same King decided to appease the Russians and ordered an end to Polish resistance. Kosciuszko and many other officers resigned, went into exile in the German city of Leipzig and began planning rebellion. When Russia and Prussia agreed upon a second partition of Poland in 1794, the exiles felt they could wait no longer. Crossing the frontier, they made their way to Cracow, the ancient capital of Poland. There on March 24, 1794—a date comparable to our July 4, 1776 in the United States—a great throng in the marketplace at Cracow proclaimed Poland’s Act of Insurrection. The Act denounced the tyrannies of Catharine the Great and King Frederick William, of Prussia, in much the same style that the Declaration of Independence recited oppressive acts of Britain’s George III.  A plaque in Crakow's Market Square marks the spot where Kosciuszko took the oath as leader of his country The Act of Insurrection named Kosciuszko commander of the people’s army and temporary dictator of the state until the war should be won. He took an oath “not to use the power intrusted to him for any personal oppression, but only. . .for the defense of the integrity of the boundaries, the regaining of the independence of the nation and the founding of universal freedom.” Unlike traditional European armies, Kosciuszko’s force was not made up entirely of professional soldiers but included thousands of Polish peasants, some armed only with their scythes. Kosciuszko became known as “Leader of the Scythe-bearers.” He adopted as his uniform the peasant’s cap and the white coat of the people of Cracow.   Army of Scythe-bearers For a short time, the Insurrection achieved unbelievable success. Superior Russian forces were defeated at Warsaw and at Raclawice. Paintings of scythe-bearers successfully charging the cannon of the enemy are as common in Polish history as American pictures of the Minutemen of Lexington and Concord. But spirit alone could not overcome the might of armament, and no foreign ally came to Kosciuszko’s aid. In the savage battle of Maciejowice on October 10, 1794, Kosciuszko’s army was crushed. He himself was seriously wounded, captured and taken a prisoner to Russia. Crippled by severe injuries to head and thigh, he remained in Russian custody for more than two years, most of the time under what amounted to house arrest in the Orlow Palace in St. Petersburg. As soon as the new Czar, Paul I, succeeded Catharine in December, 1796, Kosciuszko was freed and presented with gifts including valuable Russian furs. The American diplomat, Gouverneur Morris, was in Vienna at that time and recorded: The Emperor took his son to the apartment where Kosciuszko lay ill. He told the prisoner that he saw in him a man of honor who had done his duty, and from whom he asked no other security but his word that he would never act against him. Kosciuszko attempted to rise, but the Emperor forbade him; sat half an hour and conversed with him, told his son to esteem the unhappy prisoner, who was immediately released—the guard taken away. At the same time, expresses were sent off into Siberia, and ten thousand Poles confined there received passports and money to bring them home.  The price Kosciuszko paid for the freedom of his soldiers was exile for himself. He was never again to return to Poland. He determined to make a visit to America and he considered settling permanently in what he called: “my second country.” “The Martyr of Liberty” 1792-1794 Kosciuszko’s fight for the freedom of his nation brought him honor and tribute around the world. He was admired as a romantic hero. During the Insurrection newspapers and magazines, especially in the United States, carried jubilant stories of his triumphs and sympathetic accounts of his defeats. Upon his release from prison, he was welcomed everywhere. Sonnets to him were written by Keats and Coleridge. Byron, too, penned lines about him. A novel, Thaddeus of Warsaw became widely popular. “The Martyr of Liberty,” he was called. On leaving Russia, Kosciuszko was accompanied by the young Polish author and statesman, Julian Niemcewicz, who had served Kosciuszko in the Insurrection and had likewise been imprisoned. Also in the party was a servant whose duty it was to carry the crippled Kosciuszko about. They went first to Sweden and then to England, spending six months leisurely before undertaking the ocean crossing to the United States. Niemcewicz was an intelligent observer and a faithful diarist. He wrote day-by-day accounts of his travels with Kosciuszko. They were greeted by distinguished citizens, presented with gifts and testimonials of esteem. Kosciuszko portraits were engraved and widely sold. So were lockets, rings, tableware and other objects with the hero’s likeness or his initials.  The Russian Czar sent extraordinary orders to London where the Russian Minister arranged for a physical examination of Kosciuszko by a team of ten outstanding British doctors, including the personal physician of the King of England. After the examination in June, 1797, the physicians wrote out and signed a five page letter reporting Kosciuszko’s condition, prescribing treatment for him. This was prepared for Dr. Benjamin Rush, the celebrated Philadelphia man of medicine, and is still among the Rush papers of the Library Company of Philadelphia: General Kosciuszko received a wound at the lower part of the hind head, with a blunt Sabre, which both bruised, and most probably divided the Nerve upon the right side that supplies the posterior portion of the scalp with Sensibility. Since that time the Scalp at the upper and posterior part has been without feeling . . .Kosciuszko was visited in his room in an undistinguished London hotel by the United States Ambassador. The American born artist Benjamin West, President of the Royal Academy, visited Kosciuszko and painted a portrait of him on his couch. The Whig Club of England presented a costly sword. Citizens of the port of Bristol staged a procession in his honor and he was presented with an expensive set of silver, each piece engraved ”The Friends of Liberty in Bristol to the Gallant Kosciuszko, 1797.” He stayed at the home of the American consul, which building to this day bears a plaque commemorating the fact. And when he sailed on June 19, 1797 on the ship Adriana thousands lined the shore, cheering and waving handkerchiefs.  Kosciuszko’s Return to Philadelphia 1797-1798 It took the Adriana 61 days of rough sailing to reach Philadelphia. Kosciuszko amused himself on ship, as he often did ashore, by making simple drawings and sketches of his visitors. His rough portrait of Captain Lee, Master of the Adriana, is in a historical museum at Guilford, Connecticut, and another of the ship’s cabin boy is in a second museum at New Haven. When his ship finally arrived in the Delaware river, the welcome Kosciuszko received was no less enthusiastic than his sendoff at Bristol. Here is how Philadelphia’s Gazette told it:  Dr. Benjamin Rush immediately advised Kosciuszko and his party to leave Philadelphia to avoid an epidemic of yellow fever which had just broken out and seemed likely to match the great epidemic of 1793. President John Adams and many officials of the Federal government had fled the city, as had thousands of its native citizens. On August 30, in a rented two-horse carriage, the Polish hero left Philadelphia and was gone three months. He visited for weeks at a time with his friend and wartime commander, Horatio Gates, near New York City, and at the home of another Revolutionary General, Anthony Walton White, in New Brunswick. When the fever had subsided toward the end of November, 1797, Kosciuszko wrote Dr. Rush asking aid in finding lodgings in Philadelphia which would be inexpensive. Niemcewicz was sent ahead to make the search, and his book tells about it: Not knowing a soul, I roamed the streets a little like Benjamin Franklin . . . with his loaf of bread under his arm. With the help of Dr. Rush I found a lodging as small, as remote, and as cheap as my instructions directed.The place selected was the small brick house at Third and Pine streets which a widow, Mrs. Ann Relf, conducted as a rooming house “where students and a few others shared common lodging.” The dwelling had been put up by Joseph Few, master builder, who bought the lot in 1774. He was a member of The Carpenters’ Company of the City and County of Philadelphia, the group which offered its new meeting hall for the sessions of the First Continental Congress that same year. The house was insured in 1775 by the Philadelphia Contributionship the insurance company which Benjamin Franklin helped found.  Kosciuszko, Niemcewicz and the servant moved in on November 29, 1797. The back bedroom on the second floor of Mrs. Relf’s house was the best which the rooming house provided: the invalid Kosciuszko was established there. The windows faced south, affording sunshine and a pleasant view of the handsome brick edifice of St. Peter’s Church across Pine Street. There was a small parlor adjoining. Kosciuszko filled both rooms with his belongings, including the chest of silver from Bristol and an extensive array of military cooking and serving utensils.  The lodging house soon became one of the busiest places in the young nation’s capital, attracting a constant flow of Federal, State and City officials as well as old Army friends and well-wishers. Travelers in Philadelphia were regularly taken to Third and Pine to see and meet “that illustrious defender of the rights of Mankind”. One of them, the French exile, Moreau de Saint-Mery wrote: I again called upon General Kosciuszko. Seven or eight of us went to see him on the same day . . . Those who visited him found him either in bed or stretched out on a couch like a sick man. His lodging was a bedroom with a little antechamber before it; and since his bed and couch left no room for more than two or three people, only two or three of us could see him at a given time . . .Among the numerous callers were three banished French princes, the eldest of whom, Louis Phillipe, was later to become “Citizen King” of his nation. Another notable taken by his hosts to meet Kosciuszko was the colorful Indian Chief Little Turtle, who had come to Philadelphia to negotiate tribal boundaries with the Federal Government. He presented the Polish soldier with a ceremonial tomahawk ornamented in silver. He in turn was much taken with the spectacles he noticed in Kosciuszko’s room, and received them as a gift. Julian Niemcewicz wrote that “in the last beautiful days of March, the visits of the young ladies to Gl. (General Kosciuszko) increased.” They were truly flowers appearing at the first puff of the zephyr. All came in order to have him paint them.  One of the attractive teenagers whose likeness was drawn by Kosciuszko was Lucetta Pollock, the daughter of a distinguished veteran of the Revolution. She died in her twentieth year, but Kosciuszko’s sketch of her was kept by a friend of the family, banker-historian John F. Watson. When he wrote his Watson’s Annals, a widely-consulted book of miscellany about early Philadelphia, he mounted it in the manuscript copy which is still preserved at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

One of the attractive teenagers whose likeness was drawn by Kosciuszko was Lucetta Pollock, the daughter of a distinguished veteran of the Revolution. She died in her twentieth year, but Kosciuszko’s sketch of her was kept by a friend of the family, banker-historian John F. Watson. When he wrote his Watson’s Annals, a widely-consulted book of miscellany about early Philadelphia, he mounted it in the manuscript copy which is still preserved at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Kosciuszko and Thomas Jefferson 1792-1794 The visitor who came most often to Kosciuszko’s Philadelphia residence and became his closest American friend was Thomas Jefferson, Vice President of the United States. Jefferson wrote within a few weeks after Kosciuszko settled in the house at Third and Pine: I see him often. He is as pure a son of liberty, as I have ever known, and of that liberty which is to go to all, and not to the few or rich alone.Jefferson and Kosciusko were nearly the same age, alike in personal philosophy and political views. In Philadelphia they saw each other almost daily; after Kosciuszko returned to Europe they corresponded for nearly twenty years. Jefferson helped his friend obtain from Congress nearly $19,000 in overdue pay for his war service. Kosciuszko left the money in Philadelphia for investment by Jefferson’s banker, John Barnes. Once when Jefferson needed funds, he borrowed $4,500 of Kosciuszko’s money. Later Jefferson saved Kosciuszko’s investments by ordering a timely sale of bank stock, which later became worthless. Kosciuszko secretly planned to go to France at first opportunity. Polish exiles were organizing legions to join France in fighting against Poland’s old enemies. Although crippled, Kosciuszko felt he could help his country. The Vice President helped him obtain a passport under a fictitious name and arrange a secret journey to Paris by a circuitous route. Jefferson, for his part, thought that Kosciuszko might be able to lessen some of the tension that had brought the United States and France to the brink of war. “Jefferson considered that I would be the most effective intermediary in bringing an accord with France. “ Koscuiszko said some years later, “so I accepted the mission even if without official authorization.”Kosciuszko gave Jefferson a power of attorney and a memorandum in his imperfect English requesting the Vice President to draft a will for him and to be his executor. The original memorandum Kosciuszko wrote is in the Jefferson papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society. It became widely acclaimed as evidence of his humanity: I beg Mr. Jefferson that in case I should die without will or testament he should bye out of my money so many Negroes and free them, that the restant sum should be sufficient to give them education and provide for their maintenance.It is unfortunate that Kosciuszko made other wills in Europe later, after his death, three-way litigation developed over his estate. Not until 1852 was the matter settled by the United States Supreme Court, which then held that the Polish General died intestate so far as his property in America was concerned. The estate was awarded to descendants of his relatives in Poland, and the testator’s worthy purpose could not be carried out.  Kosciuszko gave Thomas Jefferson a bearskin and a valuable sable fur that he had brought with him from Russia. Among the Jefferson papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston are two letters from Kosciuszko with detailed instructions to care of the furs. Historians and biographers have frequently commented upon the favorite fur-trimmed greatcoat which Jefferson wore much of the rest of his life. The fur appears in a portrait of Jefferson painted by Rembrandt Peal in 1805. The original is it the New York Historical Society, with a copy at Monticello in Virginia.

Kosciuszko gave Thomas Jefferson a bearskin and a valuable sable fur that he had brought with him from Russia. Among the Jefferson papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston are two letters from Kosciuszko with detailed instructions to care of the furs. Historians and biographers have frequently commented upon the favorite fur-trimmed greatcoat which Jefferson wore much of the rest of his life. The fur appears in a portrait of Jefferson painted by Rembrandt Peal in 1805. The original is it the New York Historical Society, with a copy at Monticello in Virginia.When Thomas Sully in 1821 did the only full-length portrait of Jefferson made during his lifetime, the long fur-trimmed coat was featured and may be seen today in the painting at the library at West Point. When Rudulph Evans produced his great statue for the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, he also chose to portray the long coat and the fur from Thaddeus Kosciuszko. Thaddeus Kosciuszko was admitted to membership in the prestigious American Philosophical Society in Independence Square, Philadelphia, in 1785. Benjamin Franklin, founder of the Society, was its president. When Kosciuszko returned to Philadelphia in 1797, his companion Julian Niemcewicz was made a member.  On May 4, 1798, Thomas Jefferson was the Society’s president and chaired a meeting in this building—less than half a mile from Kosciuszko’s room at Third and Pine. Niemcewicz attended that meeting and heard Jefferson read a paper describing a new design for the mould board of a plow. Not until he returned to the house did Neimcewicz learn that Kosciuszko planned to leave for France that very night.

On May 4, 1798, Thomas Jefferson was the Society’s president and chaired a meeting in this building—less than half a mile from Kosciuszko’s room at Third and Pine. Niemcewicz attended that meeting and heard Jefferson read a paper describing a new design for the mould board of a plow. Not until he returned to the house did Neimcewicz learn that Kosciuszko planned to leave for France that very night.At 4 A.M., it is related in Niemcewicz’s book, Thomas Jefferson arrived at the house at Third and Pine in “a covered carriage”. Kosciuszko was helped inside and Jefferson accompanied him to New Castle, Delaware, where a ship was ready to sail for Europe. Jefferson helped spread the word that Kosciuszko had gone “to take the waters in Virginia”. The secret was kept in Philadelphia until September when French newspapers were received announcing his arrival in Paris. A Hero of Two Worlds  For the rest of his life, Kosciuszko hoped for freedom for his native Poland, but met only disillusionment and discouragement. He lived in Paris more than 15 years, but the Directory of the French Revolution did nothing for Poland. Later, Napoleon Bonaparte visited Kosciuszko to ask his influence in supporting French imperial plans. Kosciuszko refused Napoleon and always felt the French Emperor sought only greatness for himself. In 1815, after the downfall of Napoleon, Kosciuszko traveled to the Congress of Vienna, hoping to persuade the nations assembled there to create a new Poland. “But it all went up in smoke”, he wrote to Jefferson. Thereafter, Kosciuszko moved to the little village of Soleure in Switzerland where he died on October 15, 1817.

For the rest of his life, Kosciuszko hoped for freedom for his native Poland, but met only disillusionment and discouragement. He lived in Paris more than 15 years, but the Directory of the French Revolution did nothing for Poland. Later, Napoleon Bonaparte visited Kosciuszko to ask his influence in supporting French imperial plans. Kosciuszko refused Napoleon and always felt the French Emperor sought only greatness for himself. In 1815, after the downfall of Napoleon, Kosciuszko traveled to the Congress of Vienna, hoping to persuade the nations assembled there to create a new Poland. “But it all went up in smoke”, he wrote to Jefferson. Thereafter, Kosciuszko moved to the little village of Soleure in Switzerland where he died on October 15, 1817. His memory is kept alive in both the United States and Poland. In this country, there are important monuments in Washington, at West Point and at Saratoga; there are statues in many major cities. This statue in the park across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House in Washington shows the Polish engineer in the uniform of the Continental army, carrying his plans for the defenses at Saratoga.  In the national capitol a marble bust of Kosciuszko stands not far from the Trumbull painting depicting the British surrender at Saratoga.

In the national capitol a marble bust of Kosciuszko stands not far from the Trumbull painting depicting the British surrender at Saratoga. In Indiana, there is a county named for Kosciuszko. When Attala County in Mississippi was established in 1833, the name of the county seat was selected by a state representative who had often heard about the Polish officer with whom his grandfather had served in the Revolution. To this day the town on the beautiful Natchez Trace Parkway proudly carries the name Kosciusko, Mississippi.    In Poland, Kosciuszko’s body is entombed in the monumental Wawel Castle at Cracow, the centuries-old burial place of the Kings of Poland. Above the castle walls rises an inspiring statue of him on horseback, leading his scythe-bearers into battle. At the National Museum in the modern Polish capital of Warsaw, a Kosciuszko Memorial is visited by thousands of school children every year, just as students in the United States make historical pilgrimages to Washington. Perhaps the most dramatic monument to Kosciuszko is the huge Kopiek, or little hill, which has been built in his memory at Cracow. They wanted to erect a memorial that would be as long-lasting as the pyramids. A large stone foundation was laid just outside the walls of the old city and for three years people of Poland from all walks of life brought there the soil from all parts of their country, piling up a hill that dominates the modern city that has grown up around it.  The Polish people wanted a monument that would last as long as the Pyramids The memory of Kosciuszko has become a symbol of international friendship and goodwill between Poland and the United States. When the Polish First Secretary, Edward Gierek, paid an official visit to this country in 1974, his schedule included a wreath-laying ceremony at the monument in Washington that commemorates both Saratoga and Raclawice. Similarly, President Gerald R. Ford traveled to Cracow in 1975 to pay tribute with the First Secretary to “The Hero of Two Worlds” at the plaque that marks the spot in the marketplace where Poland’s Act of Insurrection was proclaimed and Kosciuszko took his oath as leader of his nation.  to Thaddeus Kosciuszko in Cracow, Poland, 1975 |